Blog

Big data doesn’t mean smart analysis.

01 December 2025

Predictive churn models without causal clarity risk mistaking hindsight for foresight.

Big data doesn’t mean smart analysis.

Let’s build a churn model for our hypothetical client, a streaming service.

We take the client database and look for predictors of churn*:

- Reduced usage frequency

- App uninstalls or device disconnects

- Password sharing / multiple logins

- Payment method changes (e.g., removing a card)

- Customer support complaints

- Unsubscribing from marketing emails

- Late billing

- Overcharging / hidden fees

- Refund requests

Then combine these into a predictive model.

All standard stuff that happens every day in the data analytics industry.

BUT

Too often, these models are built on signals that look predictive but are in fact ambiguous – they can be both causes of churn and consequences of churn.

That's not foresight, it's hindsight dressed up in statistics.

The Takeaway

Correlation ≠ causation.

If your churn model relies on signals that are consequences, you’ll end up predicting churn after it’s already happened.

Retention strategies demand more than pattern spotting. They require understanding causal paths – what truly drives disengagement – so you can intervene before the customer has already left.

Reduced usage frequency

- Cause: Lower engagement or declining perceived value

- Consequence: Customer has already shifted attention to a competitor

App uninstalls or device disconnects

- Cause: Removing the app reduces engagement and nudges toward churn

- Consequence: Once the decision is made, uninstalling is simply the final act

Password sharing / multiple logins

- Cause: Customer feels the service isn’t worth paying for solo, so they share costs

- Consequence: After mentally churning, they stop caring about account security and share credentials freely

Payment method changes (e.g., removing a card)

- Cause: Signals intent to reduce commitment or avoid auto renewal

- Consequence: After churn, users strip payment details to prevent further charges

Customer support complaints

- Cause: Dissatisfaction or poor experience can drive churn

- Consequence: Complaints often spike after the decision to leave

Unsubscribing from marketing emails

- Cause: Early signal of disengagement

- Consequence: Post churn, customers remove unnecessary emails

Late billing

- Cause: Business error that creates frustration

- Consequence: Once disengaged, customers ignore invoices entirely

Overcharging / hidden fees

- Cause: Pricing errors or opaque billing practices erode trust

- Consequence: Customers already on the way out scrutinise bills and notice fees

Refund requests

- Cause: Dissatisfaction with product or service

- Consequence: Refunds often mark the final step after churn is decided

Big data without causal clarity is just noise at scale.

Big Data isn’t as smart as you think.

24 November 2025

Big data without causal clarity is just noise at scale.

“Data is the new oil.”

But like oil, raw data has no intelligence.

What truly matters is the qualitative understanding of causal paths and the data-generating mechanisms behind the numbers.

Correlation may be interesting, but commercially it’s far less valuable than causation. Knowing that A causes B is actionable. Knowing only that A and B move together is often misleading.

Think of it this way: it’s not the oil (data) that drives better decision-making, it’s the engine (causal structure) that ensures we’re pulling the right levers.

Big data without causal clarity is just noise at scale. Next time, I’ll share an example that highlights the “stupidity” of big data when it’s mistaken for intelligence.

Three Research Questions That Sound Smart – but Mislead

17 November 2025

In customer research, some questions feel insightful but quietly lead us astray:

- “Why did you do that?”

Memory is a poor narrator, consumers struggle to understand their own motivations. Post-rationalisation ≠ causality. - “What do you want?”

Desire ≠ demand. People imagine futures they won’t act on. They likely don’t even know what they want. Who asked for an iPhone before it was invented? - “How would you feel if…?”

Hypotheticals are notoriously difficult to answer and lack real-world context.

These questions are probably acceptable for assessing gut-reactions, but not for making decisions.

Counterfactual simulation provides a far better way to address these questions – without asking customers to guess.

Your CX Programme Is Not a Tree

10 November 2025

Real experiences don’t branch neatly — they ripple, cascade, and collide...

Take a look at your CX measurement programme. Do you structure it like a tree?

- Branching neatly into channels, products, services etc.

- Each limb analysed in isolation

Why? (Because it’s trivial to analyse hierarchical tree-like data.)

But real experiences don’t work like that.

- We don’t think in hierarchical structures but as dynamic networks of perceptions.

- A poor experience with the app doesn’t just affect the other digital channels, it spills over to affect our perceptions of the product, service, even the brand.

When we treat CX as a tree, we miss the lateral interactions:

- A clunky chatbot makes the phone agent feel less competent

- A broken returns process taints the product itself

- A delay in delivery casts doubt on the ordering process

To truly understand experience, we need to model it as a network of perceptions.

Interlinked and capable of propagating the consequences of an experience throughout the system.

That means:

- Dual impact scores that capture both the direct and ripple effects of each touchpoint

(How does a poor experience affect satisfaction in isolation? And how does that shift when we account for the knock-on effects across the network?) - Simulation capabilities that estimate the system-wide impact of changing multiple touchpoints at once

- NOT using regression-based driver analysis to prioritise CX investment

Reality, Perception and Emotion

November 2025

“Put your hand on a hot stove for a minute, and it seems like an hour. Sit with a pretty girl for an hour, and it seems like a minute. That's relativity.”

– Albert Einstein

Not wishing to disagree with Albert Einstein, but perhaps this illustrates the difference between perceptions and reality.

Let’s talk about queuing.

The length of time spent queueing may be measured in minutes. But the truth is, it’s not the objective time spent waiting that shapes experience – it’s the perception of that time. And more than that, it’s the emotional response to the wait.

A 3-minute queue can feel like 30 if it’s stagnant, silent, and unexplained. Meanwhile, a 10-minute wait isn’t an issue if the line moves visibly, updates are shared, and empathy is shown.

🟢 Positive cues: Fast-moving queues, clear signage, updates, friendly staff, visible progress

🔴 Negative triggers: Unexplained delays, opaque systems, being passed between operators, lack of acknowledgment

It’s Rory Sutherland and the Eurostar all over again!

This of course matters not just for service design – but for measurement too.

When it comes to customer satisfaction it is not the objective reality (minutes spent queuing) but the perception that matters. That’s why surveys ask (subjective) satisfaction, not (objective) waiting time. As humans we may be quite wrong in our assessments, but that doesn’t matter – it’s how we feel that matters.

Which brings us nicely to emotions.

According to cognitive appraisal theory, when it comes to how consumers form memories and make future behavioural decisions, it’s not just the event or their perception of it that matters – but also their emotional response.

And this is why those nice touchpoint surveys (you know, “could you please rate the performance of the agent you dealt with?”) should ask not just (perceived) satisfaction, but how you felt about the experience.

Love and Networks.

October 2025

“I like him/her a lot. Thinking about his/her positives and negatives and taking a weighted sum of these accounting for their importance in a prospective partner, I’ve decided I’m in love.”

Total bollocks.

Yet that’s how we conventionally analyse CX data.

You’d be surprised just how many CX programmes use multivariate regression to prioritise improvements. Even to build dodgy ‘simulators’.

Relative importance, Shapley regression etc. It’s all just as bad.

It’s of course simple to run this sort of analysis (and bill the client handsomely) but the implications are absurd.

It assumes that consumers mentally sum up each aspect of their experience and weight them according to some internal ‘importance’ measure.

That’s of course nonsense.

“The dining room was empty and needed dusting. The staff were disinterested and the toilets filthy. Since these were facilities and service touchpoints, it didn’t put me off the marinated raw fish at all.”

You should be using networks. Not multivariate regression.

What Is. And What Could Be.

October 2025

Consumer insight excels at describing reality — but what if we could simulate the future?

You exit a meeting in a city you don’t know. You need to get to the airport.

You open Google Maps. It shows a blue dot: you are here. That’s the “what is.”

But your real question is: how do I get there?

Google Maps doesn’t just offer routes – it shows the consequences of each. Time, cost, distance. That’s what makes it powerful. You can now make an informed decision, confident in the outcome.

In consumer insight, we’re great at answering “what is.”

Who buys from us? What do they think? Where else do they shop?

But we struggle with “what could be.”

What if we changed X? What if we improved Y? What if we did both?

Counterfactual simulation mimics Google Maps: it offers paths to your desired outcome then estimates the consequences of each.

In CX, for example, it might show different ways to improve NPS – along with the cost, effort, and impact of each.

That’s how we move from describing “what is” reality to guiding “what could be” decisions.

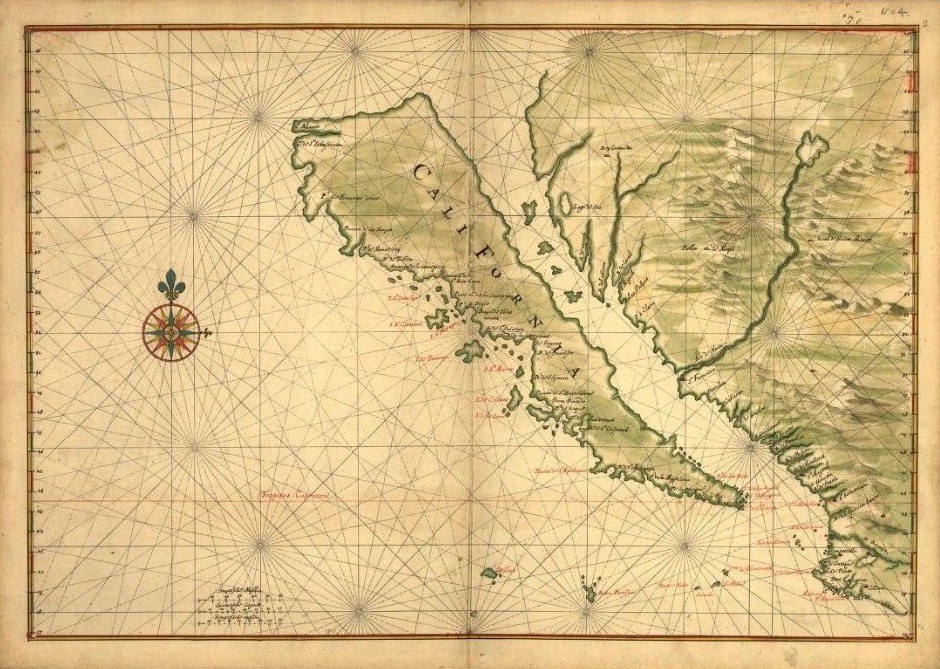

The Map Is Not the Territory

October 2025

The Menu Is Not the Meal.

Maps are abstractions – simplified representations of a complex reality. They help us plan, orient, and navigate. But:

- They are never the terrain itself

- They may be incomplete, outdated, or misleading

Theories and models function in much the same way. A theory attempts to explain; a model attempts to predict. Both are tools for understanding – but both are, by definition, simplifications.

Like maps, models and theories are not reality. They are tools – useful, but fallible. They can guide decision-making, but they can also distort it and provide confidence where perhaps there shouldn’t be.

Personally, I’m an advocate for counterfactual simulation as a better way to explain consumer thoughts and actions. It offers a depth of insight far beyond conventional analytics. But despite this, I remind myself: never lose sight of the fact we’re dealing with a representation of reality, not reality.

The solution?

- Be sceptical. Some models are useful. Some are accurate. But never assume either by default.

- Think critically. Models don’t replace judgment – they inform it. Commercial commonsense matters at least as much.

- Be humble. Even the most elegant model will fail eventually.

Is It Easier to Predict the Future or to Know the Past?

October 2025

Seems a rather simple and obvious question, right?

Past: Who won the 2005 Ashes? England.

Future: Who’ll win the 2025–26 Ashes? Care to make a prediction?

Okay, that was simple.

Let’s reverse the order…

Future: There’s an ice cube on the floor. What will happen to the ice cube in 10 minutes from now?

Past: There’s a puddle on the floor. How did this come to be?

So maybe it’s not so simple after all.

Moral of the story:

Reconstructing the past to provide causal explanations can be harder than predicting future probabilities.

Commercial implication:

Be sceptical of ‘data storytellers’ who blur (honest) turning dry facts into memorable narratives with (dishonest) inventing causality.

Question 3 for Your Next Agency Debrief

October 2025

What are the consequences of implementing your recommendations?

All research and insight debriefs need to come with recommendations. We learnt this as a grad.

But cobbled together, meaningless recommendations are worse than nothing. They mislead and give confidence where it’s not warranted.

Sure enough, you’ll get recommendations. In a beautifully crafted PowerPoint presentation.

And that’s why it’s important to tease out what’ll likely happen if you implement these recommendations. It makes for better decision-making and reduces risk. Forewarned is forearmed.

But here’s the dark secret: Most research and insight is based on observational data. Big data, market research. Whatever. It’s rarely an experiment.

And that means the consequences of implementation are unknown. That makes for poor decision-making and sleepless nights.

Question 2 for Your Next Agency Debrief

October 2025

Of the many possible recommendations you could make, why did you make this one?

This is a hand grenade. Use only under special circumstances.*

You’ve paid an agency to advise you on a CX or brand challenge. Maybe something specific. Maybe just general guidance.

They arrive, confident and polished, with a snappy presentation and firm recommendations:

“You need to focus on A. B isn’t important. Segment 3 needs this. Do that. Don’t do this.”

But here’s the reality:

Your organisation faces infinite possible actions.

Each has a cost, a return, and a ripple of consequences** – some obvious, some unknowable.

If your agency has done the hard work – mapped options, weighed trade-offs, and built a coherent commercial case – then they’ve earned their recommendation.

They might be wrong, but they’ll hit your question over the boundary for six. You owe them a post-debrief drink.

If they haven’t?

If they’ve picked a path without exploring the rest, skipped the consequences, and called it “best” by default – then a little bodyline bowling seems entirely reasonable.

* Only for consultancies, not data collectors.

Only when you’re paying handsomely for the advice.

Only directed to the most senior person – not their overworked staff.

** We’ll come back to how we anticipate likely consequences another time.

Are Your Agency’s Recommendations Based on Experimental or Observational Data?

September 2025

I know – I know. “Correlation vs. causation”, a statistical nicety, right? Wrong...

It's the difference between guessing and knowing.

Experimental data involves deliberate manipulation and control.

Think A/B testing, conjoint analysis, randomised trials.

These demand careful design, clear hypotheses, and controlled conditions to isolate variables.

Consequence: We can say “X causes Y”. That's causal inference – the gold standard.

Observational data, by contrast, is passive.

Think CX or brand trackers, social listening, or most Big Data analytics.

We observe patterns, trends, and associations – but without intervention.

Consequence: We can say “X is associated with Y”, but not “X causes Y”.

Moral of the story

If it's not an experiment, treat the findings for what they are: interesting observations, not actionable truths.

Be exceedingly cautious about drawing conclusions – let alone making decisions – based on them.

Of course, strategic CX and brand challenges rarely lend themselves to experiments.

They're too costly, impractical, or commercially disastrous:

“Let's see the impact of deliberately losing these customers' bags.”

Fortunately, there’s a middle ground:

In CX and brand analytics, Bayesian belief networks infer likely causal drivers from observational data – delivering causal plausibility when experiments aren't viable.

But to many, that's witchcraft.

We'll explore this dark magic another time.

Three Questions to Ask at Your Next Research Agency Debrief

September 2025

That is, if you want to trust what you’re being told...

- Are your recommendations based upon experimental or observational data?

- Of the many possible recommendations you could make, why did you make this one?

- What are the consequences of implementing your recommendations?

Next time we’ll look at why these questions are so important and whether you should trust the recommendations.

What Three Tools Are Pivotal to Making Informed Data-Driven CX Decisions?

September 2025

Hint: they’re not the ones you think they are...

Previously we revisited the Doorman Fallacy and extended this to include much of CX decision-making. We then introduced the three impediments to making informed, data-driven CX decisions:

- Changing just one perception (e.g. satisfaction with your telco’s network reliability) causes many other perceptions (VFM, trust, ease…) to change in unpredictable ways.

- The perception changes will ultimately affect ‘outcome’ perceptions (NPS) and consumer behaviours (churn), but we’re not privy to the mental accounting behind these decisions.

- Even if we can estimate the consequences for, say, NPS, we’re speaking the wrong language. Businesses decide on £/$-value, and we’re talking about satisfaction.

Without solving these three challenges we cannot truly have confidence in our decision-making.

The answer to the question “what will happen if we do X?” will remain “we’re not sure, but we can hope…”

That’s no way to run a business. It’s a poor answer from the multi-billion-dollar research and insight industry. But it’s where we are today.

What we need is a decision-support solution for CX.

But a special one. A causal decision support solution using observational data (your existing market research!).

- Causal in that it tells us what happens if we act (i.e. intentionally change the experience)

- Observational in that most CX (and brand) decisions cannot be tested using A/B experiments (we can only observe how things are right now)

This decision-support solution must incorporate three tools:

- A mechanism to identify the perception cascade path:

“If we change the performance of X (and Y and Z…), what other perceptions will change?” - A modelling tool that can “sum up” these changes and predict wider consequences (NPS, loyalty etc.) using observational data:

“Having noted the likely consequences of this scenario, how will the consumer react?” - The capability to factor in £/$ costs and returns in the estimates:

“It’ll cost us $10.45 per customer to improve this, how does that compare with the increase in LTV?”

Only by addressing each of these can we make informed, data-driven CX decisions.

Would you like to know more?

Arguing with Finance

September 2025

Why does short-termism win? Why do other professions have better tools? Why is CX so hard to justify...

Why is it easier to justify investment in cost-saving automation than in human assets intended to deepen emotional engagement and satisfaction?

Why does short-termism and cost-cutting so often win over investment in the customer experience?

Why do other professions have decision support tools and greater confidence in their decision-making?

Why is CX decision-making so bloody difficult?

Why is it so hard to get an answer to the question “what will happen if we do [this]?”

The reasons may be found in just one word: perceptions.

It is our perceptions (and past behaviours) that drive our decision-making, not objective reality.

We care less about how many minutes we stood in the queue and more about how long it felt like.

There are three ways in which consumer perceptions impede our ability to make decisions and win arguments with Finance:

- Changing just one perception causes many other perceptions to change in unpredictable ways:

If your bank were seen as being less traditional, more modern and youthful, how might this affect your perception of their reliability and trustworthiness? - The perception changes will ultimately affect ‘outcome’ perceptions (NPS, CSat., Preference etc.) and consumer behaviours, but we’re not privy to the mental accounting behind these decisions (so we pretend that it is additive):

“I like him/her a lot, thinking about his/her positives and negatives and taking a weighted sum of these accounting for their importance in a prospective partner, I’ve decided I’m in love.” - Even if we can estimate the consequences for, say, NPS, we’re speaking the wrong language. Businesses decide on £/$-value, and we’re talking about satisfaction:

“So let me get this straight, if we replace the front of house staff with a robot we’ll save $10M over five years, and you’re telling me this might somehow affect ‘customer satisfaction’ and ‘brand perception’?”

So, what’s the answer? Keep second-guessing the consumer and hope we’re right / make up the numbers / hope we find a new job before we’re proven wrong?

We’ll investigate this next time.

Revisiting the Doorman Fallacy: A Lesson for CX

September 2025

You already know the start of this*, so I’ll keep it snappy.

A hotel replaces its doorman with an automatic door to save money. On paper, this looks efficient. But the doorman also:

- Greets guests warmly

- Hails taxis

- Carries luggage

- Signals prestige and service quality

Removing him diminishes the guest experience and brand perception – costs that aren’t easily measured.

The doorman fallacy provides a welcome opportunity to laugh at management consultants and accountants who, in Oscar Wilde’s words, “know the price of everything and the value of nothing”.

For those of us in CX we might widen the moral of the story somewhat:

Making changes to a single touchpoint may have wider consequences for experience and brand perceptions (and resultant behaviours) than we anticipated.

And that is the trouble with CX decision-making:

- Every alteration to the experience (sacking the doorman) comes with the potential to change multiple consumer perceptions.

- The nature of these changes (brand premium, safety, convenience etc.) is difficult to anticipate, and their magnitude seemingly impossible to predict.

- Somehow the totality of these changes may result in different consumer behaviours (e.g. reduced loyalty), but we don’t understand how consumers perform this mental arithmetic.

- Since we can’t quantify the likely consequences, we can’t make an informed decision, trading off costs and benefits.

That makes CX decision-making rather challenging to say the least.

Next time we’ll introduce and unpack the three impediments to making informed, data-driven CX decisions.

* Credit of course goes to Rory Sutherland for introducing the Doorman Fallacy.

A nice explanation in under a minute:

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/_2KCzBMz1R0

Perception Cascades and Tim Revisited

May 2025

Last time we introduced Tim. Impatient Tim.

And we saw how changing just one perception, impatience, set off a cascade of perception changes.

We came to see Tim as not just Impatient but likely Pushy, Selfish, Arrogant… even Successful and Determined.

How do we know this?

We’re familiar with these concepts and have had many years to observe the behaviours of our fellow men and women. Noting the way in which one trait might indicate another.

But what if we’d just arrived from Mars, having never met a human? How might we understand this perception cascade?

A shortcut to years of observation, we could map associations between perceptions (Impatient often implies Pushy) and then use simulation* to trace the effect a change in one or more perceptions has on others. Using this even our Martian friend would know that Tim’s probably going to be a little arrogant.

These two steps are critical:

- First mapping the relationship between perceptions.

- Then using this map to mimic human thinking via simulation.

Another day we’ll delve into the commercial applications of mapping and simulation.

Perception Cascades and Tim

May 2025

Last time we talked about simulation.

For now, let’s forget about picking marbles from jars and instead talk about people and the seemingly illogical way in which they think.

There are many factors that determine our behaviours: circumstances, values, perceptions…

CX and brand can’t do much about the first two, but they can alter perceptions.

Perceptions are truly fascinating. They’re not objective reality, but our interpretation or understanding of reality.

It’s not the objective experience (minutes waiting in a queue) but the perception (they don’t care about their customers) that makes us churn.

Likewise, it’s not that your brand “fights for fair” or “goes the extra mile” that drives consideration, it’s that consumers perceive it to be so.

Change one or more perceptions and they cascade to change others. The interaction between perceptions is rather complicated.

If I tell you that Tim is ‘a little impatient’…

…that perception cascade has just happened in your brain.

Right now.

You might now believe that Tim is:

- Pushy

- Selfish

- Slightly Arrogant

- Perhaps even Successful or Determined

What if I also told you that Tim…

Is a chronic worrier

and

Volunteers at an old folk’s home

Further perception cascades occur. We add to or update our perceptions of Tim.

So, if your local supermarket decides to make changes to their range, improve availability, add more express lanes but push up prices a little, what’ll happen to your perceptions of, say, value for money or convenience or NPS? Will you be more likely to remain loyal?

And that’s what we use networks and simulation for.

We first map the flow between perceptions…

…then use this to simulate counterfactuals, like the supermarket example.

By doing this we may anticipate the consequences of our decision making.

What is Simulation?

May 2025

Do you know what makes simulation and network analysis special?

If you work in CX or brand, why should you even care?

I’ve been asked this on several occasions recently so perhaps an explanation is in order.

Let’s begin with simulation.

If I give you a jar of 80 red and 20 black marbles and ask you to randomly draw out 10 marbles with replacement, how many reds will you get? If you say “around 8” you’ve used a model:

Expected number of reds = (10 * (80 / (80 + 20)) = 8

If you sit at the kitchen table and repeat this 100 times with a jar of marbles, you’ve used simulation.

Models are great for simple problems but not for complex problems. That’s where computer simulation is used. We replace the jar and marbles with a computer and run millions of simulations instead.

But that’s only part of the story. Next time we’ll talk about perceptions…

Six Benefits of a Holistic CX Programme

May 2025

Measurement programmes don’t always align with the real experience — here’s why holistic thinking matters...

I’m a huge fan of joined-up, holistic thinking. Nowhere more so than in customer experience where measurement programmes can sometimes fail to align with the real experience.

So, before I inflict upon you my proposed solution, let’s first consider six benefits of a holistic CX programme…

- Seeing the big picture. Contextualising each aspect of the experience and its relationship to the whole.

- Customer centric thinking. Customers don’t neatly bucket their experiences by channel or touchpoint. A holistic CX programme supports putting the customer at the heart of decision-making.

- Supporting ideation and strategy. Mapping relationships between experiences, perceptions and behaviours lends itself to focused ideation and more directed conversations.

- Breaking down silos. Insight that spans multiple business functions supports inclusive, joined-up solutions.

- Understanding consequences. Tracing paths from business actions to consumer outcomes helps to identify likely consequences.

- It’s the antidote to forensic detail. Sure, knowing the Furniture department of the Oxford St. store performs poorly on a Tuesday morning is helpful. But a constant focus on the detail can sometimes miss the bigger picture.

Five Ways to Make Your CX Programme More Holistic

April 2025

Too often CX programmes reinforce the very silos they’re supposed to be breaking down...

- Get your surveys to hold hands

Your surveys should include ‘hooks’ allowing data and findings to be integrated with other surveys. Each survey represents a tile, your integrated CX programme is the mosaic. - Touchpoint surveys aren’t enough

Single question pulse surveys and closed-loop feedback plays an important role in CX, but it’s operational, not strategic. You’ll get far greater value by fully integrating these with a wider relationship tracking programme. - CX and brand shouldn’t be viewed in isolation

Experiences shape brand perceptions, brand perceptions frame experiences. Stop treating them as independent systems. Your CX programme should reflect the interaction between brand perceptions and experiences. - Think in terms of networks, not trees

The inverted tree structure so beloved of CX programmes represents a siloed, hierarchical relationship between experiences. That’s not how consumers think. Perceptions don’t obey linear algebra; to understand customers we should map experiences using networks. - Think like an ad man, not an engineer

Consumers base their decision-making on perceptions, not objective reality. You’re seeking to improve the perception of the experience, not necessarily the experience. Think how to create not just tangible value, but also intangible value for customers.

We’ll unpack what these mean in practical terms over the coming weeks.

Customer Experience Is But an Illusion

April 2025

Perhaps we’re approaching CX all wrong...

Perhaps we're approaching CX all wrong, as though it's an engineering problem, when we should be thinking like illusionists.

Your CX programme isn’t grounded in objective reality; it’s merely reflecting the subjective perceptions of your customers.

Consider this. Your satisfaction with every aspect of a product or service is coloured by a myriad of other influences: the brand, your values, previous experiences, your behaviours. Each of these interact with one another in a complex web of feedback loops.

The implications are fascinating.

- We should perhaps think in terms of networks of interacting events, perceptions and behaviours. Not silos or linear models or tree structures.

- CX measurement programmes could take a much wider interpretation of ‘experience’ incorporating brand, experiences, perceptions, events and behaviours.

- Each element of the CX programme would be integrated into a single, holistic model.

"One Simple Way to Make NPS More Relevant"

April 2025

Or, an argument for “Brand Hate” — repurposing NPS to suit your business model...

Okay, you measure recommendation and use this to report NPS. That’s not going to change.

But you must admit, NPS is something of a blunt instrument. Simply subtracting % Detractors from % Advocates doesn’t make a universally applicable metric.

Instead, we work with what you have. You take the 0–10-point recommendation question and repurpose it for your needs.

How?

- You’re a utility company. All your customers want is for the water / gas / electricity to work (and if it doesn’t, you put it right quickly). If you want to reduce churn, just don’t cock it up. Here your headline metric might be % Detractors. You thus focus on getting the basics right.

- You’re Apple. You want to cross-sell and up-sell to your adoring customers. So what if I think your products represent style over substance, enough customers adore your brand to queue in the snow to buy the latest product. You don’t care about Detractors, just the Advocates. Here your headline metric could be % Advocates. You focus on being brilliant for those who are open to your brand.

- You’re a supermarket and want to maintain loyalty. (Ignoring all the external factors) it’ll be harder for competitors to steal away your customers if you’re doing a great job. And letting your customer down will certainly make it harder to retain them. You’ll want to increase Advocacy and reduce Detractors. Reporting both Detractors and Advocates (not subtracting them!) will work for you. You’ll focus on both fixing the problems and delighting your customers.

- You’re a major sports team. Your value is in creating an army of adoring fans who’ll drive sales and sponsorship. Potentially nothing less than 10/10 will do*.

Thus, you’ll likely measure the percentage of 10/10’s and focus on creating high emotion amongst them.

* In fact, sports teams are a little odd in that it’s probably necessary to have an army of detractors too**. Who wants to support a bland team that everyone else likes too? Isn’t the emotion partially generated by the fact that every run, try or goal your team scores causes pain to the opposition fans? It’s war after all. So maybe a second metric. Brand hate anyone?

** There are doubtless exceptions. Growing up in the Antipodes, weren’t the West Indies everyone’s second favourite team?

"Rotten food and rude staff"

April 2025

Not long ago my dear old Mum opened a pack of chicken breasts only to discover they’d gone off. She’d not noticed the best before date when shopping and had purchased what must have been an older pack.

Better stock rotation and making the short expiry date clearer would have certainly helped. But these things happen.

My Mum, much like her eldest, being prone to venting on occasion pointed out it wasn’t the first time she’d been caught out. That crackers purchased were often broken, that when she’d previously taken back faulty goods she’d been met with indifference, that the staff often lacked basic manners and didn’t make eye contact etc.

Etc.

Etc.

Ultimately, Mum blamed poor staff training for all the ills she’d suffered at the hands of the supermarket. Some, to be fair, was, but out of stocks, price increases, limited availability of specialist items certainly wasn’t.

That’s what I find interesting.

Consumer research would have told us that* perceptions of the staff were very low; the rest of the experience was perhaps adequate. Key driver analysis would have pinpointed staff as a major driver of dissatisfaction. Nice.

Except that this misses the point. ‘Staff’ was acting as a lightning conductor, collecting much of the blame for other failings.

Were we to have analysed this holistically, we’d have seen strong perception flows between ‘staff’ and numerous other touchpoints (availability, range, product quality, value for money…)

Better, we could have decomposed the direct effect of staff performance on overall satisfaction versus the wider cascade effect. This would have alerted us to the problem being more than just one of staff performance.

Using holistic analysis, the supermarket could identify cross-departmental areas for cooperation and improved training. Helping to break down silos.

Some thoughts…

- Seemingly irrational** perceptions, not objective facts, drive consumer decision making.

- Consumers don’t isolate perceptions of their experience into neat buckets (channel, product, service etc.) Neither should your CX programme.

- Reductionist CX models that mimic your business structure (tree-like models which compartmentalise and then roll up to CSat / NPS) may be mathematically simple, but they miss the ‘sideways’ movement between business functions. Be sceptical of their recommendations.

* Assuming the other shoppers were like my mother…

** No Mum, I’m not saying you’re irrational. Ever. Promise.

The Problem with NPS

April 2025

The problem with NPS isn’t that it’s not correlated with customer satisfaction, the problem is it is.

Reading the below the other day I nearly spat out my tea...

“There's no correlation between Net Promoter Score and customer satisfaction or increased profit.”

Seriously?!

I got no response when I challenged this.

Okay, let’s leave profit out of this for now. Too many other factors are involved here.

Looking at some old projects I found correlations of between 70% and 98% (yes, 98%!) between Satisfaction and Recommendation (the metric behind NPS).

It’s painfully easy to find fault with NPS. So here are some things to reflect on when considering or using NPS:

- If there’s such a high correlation with Satisfaction why measure and report NPS as well?

- Consultancies earn good money implementing NPS programmes. Refer them to 1. and ask what additional benefit NPS will bring.

- (I know you know this). NPS is the difference between Advocates and Detractors. If you’re going to use NPS, report these two figures separately.

- Most CX outcome metrics (satisfaction, NPS, effort, ease…) are highly correlated. Philosophical discussions about their differences without first analysing them using your own survey data is a bit pointless.

- Without linking CX metrics to $/£ value it’s all very interesting, but somewhat theoretical.

Does your customer or product experience need to be perfect?

April 2025

How worthwhile is it to aim for perfection versus just being very good? Or even being exceptional in just one or two areas?

(Health warning: this one’s a wee bit analytical, but hang in there…)

We’ve measured 27 features plus overall satisfaction for a SaaS product on a 1–7 scale.

Do we really need users to rate a perfect 7/7 for everything? What’s good enough?

Example 1 (blue): average overall product satisfaction vs. average feature satisfaction.

Conclusion: Every little helps. A 1% improvement in feature satisfaction implies a 1% increase in overall satisfaction. Simple.

Example 2 (green): same outcome vs. percentage of features rated 7/7.

Conclusion: A lot of customers (41%) don’t think any of your features are perfect. But they’re still rating your product a (just about) adequate 55% overall. If you had 10 features rated 7/7 you’d potentially increase this to 84% overall. But is all that effort worth it?

But is average overall satisfaction a suitable outcome variable? If you want to prevent churn, it might be. But if you want your customers to do something extraordinary (like cross-sell), you may prefer to measure how many are thrilled with your current product. So, let’s instead measure the proportion of customers rating overall satisfaction as 7/7.

Example 3 (red): proportion of customers rating overall satisfaction as 7/7 vs. number of perfect features.

Conclusion: Without achieving a perfect rating on at least a few features, you’ve no hope of having a delighted customer. Even a single 7/7 shifts the outcome from 1.2% to 4.8% — an uplift of 4×. You’d be wasting your time seeking perfection — getting around half of features rated 7/7 is surely enough.

So, if you’re looking to up-sell, potentially you must be brilliant at several things. But not perfect by any means.

Moral of the story:

- Different business objectives may require us to consider different metrics (even if they’re derived from the same question).

- Those different metrics may infer quite different strategies.

- Just looking at means really isn’t enough.

Visualising Cultural Similarities as a Network

March 2025

A fresh take on the Inglehart–Welzel cultural map — reimagined as a network to explore similarity...

Here’s a nice way to visualise similarities between countries.

I’ve used the data behind the famous Inglehart–Welzel cultural map but reimagined as a network instead.

It’s a nice way to compare just about anything… countries, product ranges, brand perceptions, even people.

I’m looking for a few proof-of-concept test cases. Drop me a line if you think your business could benefit from this.

23 things I wish they'd told me about CX

March 2025

A field guide for consultants and analysts navigating the messy, world of customer experience...

- Immerse yourself in the client’s sector.

- Be the customer, visit their store, observe, buy their product, try the website

- Bring the brand up in conversation and listen

- Read up on the brand and sector before you ask a question

- Look outwards, not inwards.

- The client has a warped view of their sector, you’re a consultant so your views are warped too

- Try to think of things from the POV of the customer, your mother, a friend who’d shop there etc.

- Use plain English, not corporate speak that seeks to obfuscate

- Ask the obvious questions that no one else asks (assuming you’ve prepared yourself first)

- Consumer decision making is driven by perceptions, not objective reality.

- That can make things tricky, perceptions obey different rules

- Learn these rules and how to work with perceptions

- Never forget that your role is to increase customer perceived value, not do the customer’s bidding

- Don’t expect customers to tell you why they did something or what they want. They probably don’t entirely know themselves.

- You’ll need to infer this from what they can reliably tell you

- That can be tricky. But if it were as easy as asking, the client wouldn’t need you anyway

- Posting on LinkedIn that X% of consumers say they want… helps flag to prospects that you don’t really understand consumers

- (If you’ve been doing this long enough and know the sector) then instinct, commercial nous and commonsense are to be valued at least as highly as analytics.

- But since you’re going to use numbers, do it properly

- Just because you / your agency / the client makes use of ‘advanced analytics’ it doesn’t make it the right tool for the job.

- Clever analytics is often used as a cover for a lack of thinking or understanding

- If you don’t see the value, ask for a plain English explanation

- Every decision involves a trade-off.

- Identify this early on and try to measure both sides of the equation: efforts vs. returns, returns vs. opportunity cost etc.

- Doing this helps your client to understand the consequences of any decision

- What gets measured gets improved.

- What’s used to set bonuses is usually gamed

- Be smart about what’s measured and ensure that targets reflect both sides of the equation

- Customer journeys are more insightful than touchpoints or channels alone.

- Where possible, design questions and analysis around a task or purpose, not how the organisation is structured

- A joined-up, customer-centric view of the experience lends itself to finding a holistic solution.

- Channel specific monitoring programmes have their place, but they won’t help to address inter-departmental failings or break down silos

- Models shouldn’t confine themselves to traditional CX but the entirety of the customer experience including brand and communications

- The average isn’t a very helpful metric

- Neither is NPS for that matter

- Distributions are far more insightful. Even banding metrics into high / medium / low is a good start.

- There are more important things than statistical significance

- Practical and commercial significance for instance

- Trends and patterns may be significant, even if an individual data point isn’t

- Besides, one may manipulate statistical significance using sample size and the margin of error calculations you see are often wrong anyway

- Outcome metrics need to be aligned with business objectives. Obviously.

- Ideally there should be a proven link (using the client’s data, not in a white paper) between a chosen research-based metric and a behavioural outcome

- It’s difficult. Most research-based outcome metrics are highly correlated. Chances are that ‘strategic’ move from CSat to NPS swapped two metrics that were 95% correlated anyway

- Understanding what drives different outcome metrics is essential if the client is to improve them.

- Most driver metrics are highly correlated with each other

- Every perception affects every other perception.

- You need to deal with this if you’re to help your client

- A lot of your work will involve helping your client to prioritise where to focus their efforts.

- Many factors come into play here. Shapley regression and relative importance analysis only addresses a few of these.

- Consider usage as well as satisfaction. Does the (expensive) interaction with a staff member add some longer-term emotional value that an automated interaction doesn’t?

- Prioritisation needs to go all the way down to specific actions.

- “Empowering the customer” or similar shite doesn’t make for an actionable recommendation

- You need to be specific: do X, don’t do Y. If A happens, you must do B.

- Putting a $/£ value on everything will aid decision making and help CX to be taken seriously by the CEO and CFO.

- A business case based on costs, revenue and ROI is a lot more compelling than one that references ‘satisfaction’

- It is however tricky, time-consuming and requires a lot of subjective judgement

- Even if you can’t put a financial value on everything, at least attempt to estimate effort and returns.

- Some experiences cost less to get right than others

- It’s probably easier to take a 1/10 to a 2/10 than 9/10 to 10/10

- Very likely there’s not much difference in churn rates for 6/10 vs. 10/10 satisfaction

- Most things in life aren’t linear, your analysis shouldn’t pretend they are.

- There are tipping points, diminishing returns, hygiene factors, delighters etc.

- Each requires a different focus. Often a minimal improvement in the right spot is all that’s needed.

- Simply treating relationships as linear ignores this

- Most regression tools used in CX analysis are linear

- When setting targets, they should be internally consistent and balanced.

- Every part of the experience influences every other part of the experience. It’s four-dimensional Whac-A-Mole.

- Simply setting an arbitrary target and a ‘stretch’ target risks creating an impossible outcome and wasting resources where they’re not needed.

- Low correlation doesn’t mean there’s nothing important to see.

- Interactions often show up as having limited correlation but, when controlled for may be very important

- For some taking on more responsibility may be a major factor in job satisfaction, for others it’s the opposite. Most driver analysis techniques will miss this.

- Run analysis for as many groups as possible.

- But to keep things simple, only report what the base result shows unless a particular group deviates in an important and commercially relevant way

- Don’t make the mistake of just reporting anything statistically different

- Being able to sense-check CX investment requires one to predict consequences and examine counterfactuals.

- That’s tricky but incredibly valuable to your clients at the same time.

- Equally important is the ability to predict unintended consequences for any CX decision.